In the second post of this series we introduced an incident response challenge based on the static analysis of a suspicious executable file. The challenge featured 6 indicators that needed to be extracted from the analysis in order to create a YARA rule to match the suspicious file. In part 3 we will step through YARA’s PE, Hash and Math modules functions and how they can help you to meet the challenge objectives. Lets recap the challenge objectives and map it with the indicators we extracted from static analysis:

In the second post of this series we introduced an incident response challenge based on the static analysis of a suspicious executable file. The challenge featured 6 indicators that needed to be extracted from the analysis in order to create a YARA rule to match the suspicious file. In part 3 we will step through YARA’s PE, Hash and Math modules functions and how they can help you to meet the challenge objectives. Lets recap the challenge objectives and map it with the indicators we extracted from static analysis:

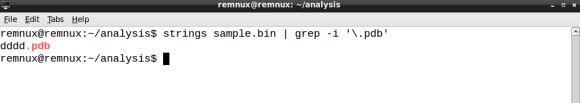

- a suspicious string that seems to be related with debug information

- dddd.pdb

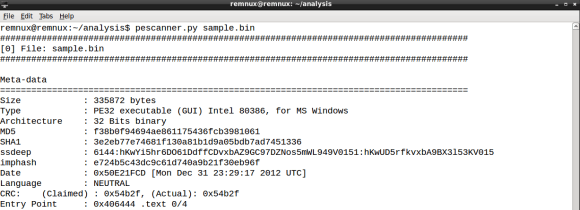

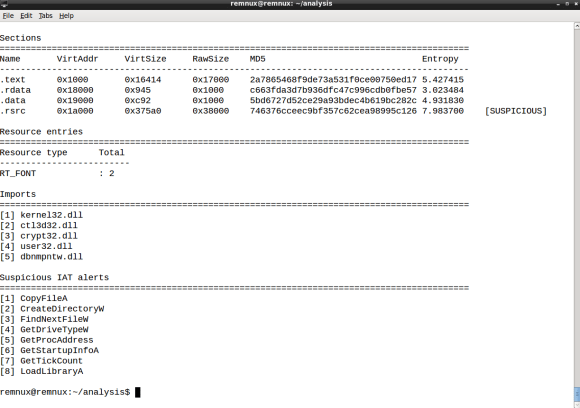

- the MD5 hash of the .text section

- 2a7865468f9de73a531f0ce00750ed17

- the .rsrc section with high entropy

- .rsrc entropy is 7.98

- the symbol GetTickCount import

- Kernel32.dll GetTickCount is present in the IAT

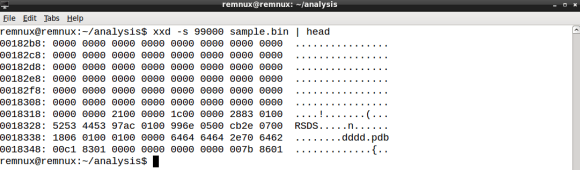

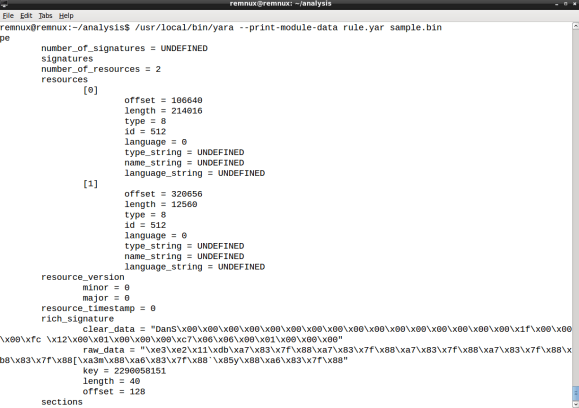

- the rich signature XOR key

- 2290058151

- must be a Windows executable file

- 0x4D5A (MZ) found at file offset zero

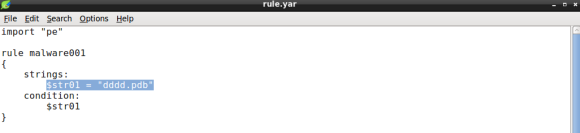

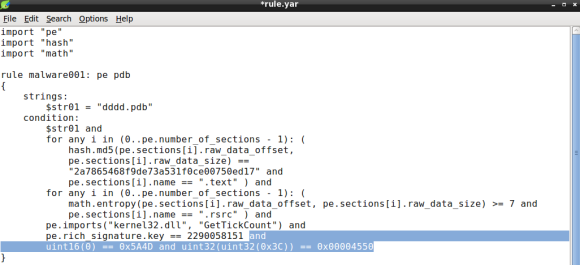

In part 2 we created a YARA rule file named rule.yar, with the following content:

import "pe"

If you remember the exercise, we needed the PE module in order to parse the sample and extract the Rich signature XOR key. We will use this rule file to develop the remaining code.

The debug information string

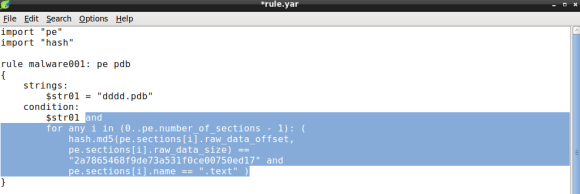

In part 1 I have introduced YARA along with the rule format, featuring the strings and condition sections. When you add the dddd.pdb string condition the rule code should be something like:

The code above depicts a simple rule object made of a single string variable named $str01 with the value set to the debug string we found.

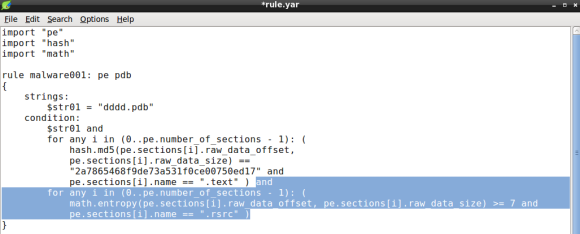

The section hash condition

Next item to be added to the condition is the .text section hash, using both PE and HASH modules. To do so we will iterate over the PE file sections using two PE module functions: the number_of_sections and sections. The former will be used to iterate over the PE sections, the latter will allow us to fetch section raw_data_offset, or file offset, and raw_data_size, that will be passed as arguments to md5 hash function, in order to compute the md5 hash of the section data:

The condition expression now features the for operator comprising two conditions: the section md5 hash and the section name. In essence, YARA will loop through every PE section until it finds a match on the section hash and name.

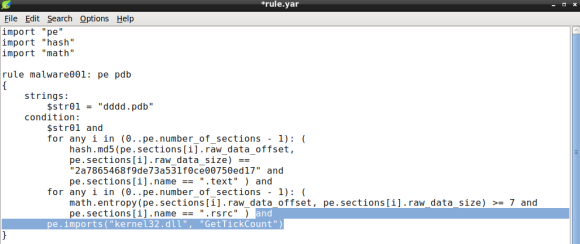

The resource entropy value

Its now time to add the resource entropy condition. To do so, we will rely on the math module, which will allow us to calculate the entropy of a given size of bytes. Again we will need to iterate over the PE sections using two conditions: the section entropy and the section name (.rsrc):

Again we will loop until we find a match, that is a section named .rsrc with entropy above or equal to 7.0. Remember that entropy minimum value is 0.0 and maximum is 8.0, therefore 7.0 is considered high entropy and is frequently associated with packing [1]. Bear in mind that compressed data like images and other types of media can display high entropy, which might result in some false positives [2].

The GetTickCount import

Lets continue improving our YARA rule by adding the GetTickCount import to the condition. For this purpose lets use the PE module imports function that will take two arguments: the library and the DLL name. The GetTickCount function is exported by Kernel32.DLL, so when we passe these arguments to the pe.imports function the rule condition becomes:

Please note that the DLL name is case insensitive [3].

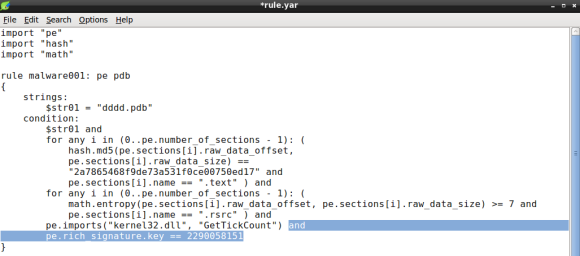

The XOR key

Our YARA rule is almost complete, we now need to add the rich signature key to the condition. In this particular case the PE module provides the rich_signature function which allow us to match various attributes of the rich signature, in this case the key. The key will be de decimal value of dword used to encode the contents with XOR:

Remember that the XOR key can be obtained either by inspecting the file with a hexdump of the PE header or using YARA PE module parsing capabilities, detailed in part 2 of this series.

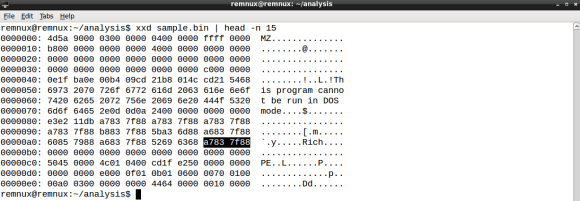

The PE file type

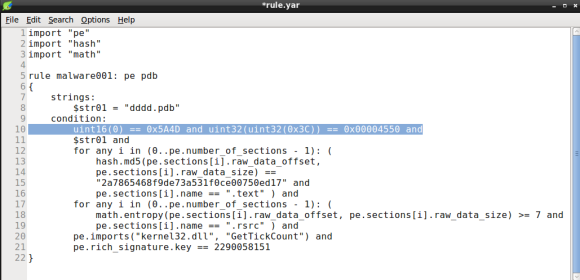

Ok, we are almost done. The last condition will ensure that the file is a portable executable file. In part two of this series we did a quick hex dump of the samples header, which revealed the MZ (ASCII) at file offset zero, a common file signature for PE files. We will use the YARA int## functions to access data at a given position. The int## functions read 8, 16 and 32 bits signed integers, whereas the uint## reads unsigned integers. Both 16 and 32 bits are considered to be little-endian, for big-endian use int##be or uint##be.

Since checking only the first two bytes of the file can lead to false positives we can use a little trick to ensure the file is a PE, by looking for particular PE header values. Specifically we will check for the IMAGE_NT_HEADER Signature member, a dword with value “PE\0\0”. Since the signature file offset is variable we will need to rely on the IMAGE_DOS_HEADER e_lfanew field. e_lfanew value is the 4 byte physical offset of the PE Signature and its located at physical offset 0x3C [4].

With the conditions “MZ” and “PE\0\0” and respective offsets we will use uint16 and uint32 respectively:

Note how we use the e_lfanew value to pivot the PE Signature, the first uint32 function output, the 0x3C offset, is used as argument in the second uint32 function, which must match the expected value “PE\0\0”.

Conclusion

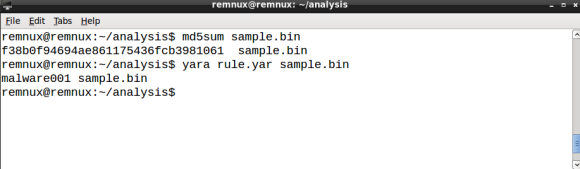

Ok! We are done, last step is to test the rule against the file using the YARA tool and our brand new rule file rule.yar:

YARA scans the file and, as expected, outputs the rule matched rule ID, in our case malware001.

A final word on YARA performance

While YARA performance might be of little importance if you are scanning a dozen of files, poorly written rules can impact significantly when scanning thousands or millions of files. As a rule of thumb you are advised to avoid using regex statements. Additionally you should ensure that false conditions appear first in the rules condition, this feature is named short-circuit evaluation and it was introduced in YARA 3.4.0 [5]. So how can we improve the rule we just created, in order to leverage YARA performance? In this case we can move the last condition, the PE file check signature, to the top of the statement, by doing so we will avoid checking for the PE header conditions if the file is an executable (i.e. PDF, DOC, etc). Lets see how the new rule looks like:

If you like to learn more about YARA performance, check the Yara performance guidelines by Florian Roth, as it features lots of tips to keep your YARA rules resource friendly.

References

- Structural Entropy Analysis for Automated Malware Classification

- Practical Malware Analysis, The Hands-On Guide to Dissecting Malicious Software, Page 283.

- YARA Documentation v.3.4.0, PE Module

- The Portable Executable File Format

- YARA 3.4.0 Release notes

I remember back in 2011 when I’ve first used YARA. I was working as a security analyst on an incident response (IR) team, doing a lot of intrusion detection, forensics and malware analysis. YARA joined the tool set of the team with the purpose to enhance preliminary malware static analysis of portable executable (PE) files. Details from the PE header, imports and strings derived from the analysis resulted in YARA rules and shared within the team. It was considerably faster to check new malware samples against the rule repository when compared to lookup analysis reports. Back then concepts like the kill chain, indicator of compromise (IOC) and threat intelligence where still at its dawn.

I remember back in 2011 when I’ve first used YARA. I was working as a security analyst on an incident response (IR) team, doing a lot of intrusion detection, forensics and malware analysis. YARA joined the tool set of the team with the purpose to enhance preliminary malware static analysis of portable executable (PE) files. Details from the PE header, imports and strings derived from the analysis resulted in YARA rules and shared within the team. It was considerably faster to check new malware samples against the rule repository when compared to lookup analysis reports. Back then concepts like the kill chain, indicator of compromise (IOC) and threat intelligence where still at its dawn.